Quentin Grafton and Safa Fanaian, The Australian National University

‘Too much, too little, and too dirty’ sums up the problems underpinning the growing world water crisis. It’s also the title of a just published global review describing the causes and possible responses to this global crisis. Quentin Grafton (formerly a commissioner and lead expert of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water which delivers its final report in 2024), and Safa Fanaian use four framings to highlight some of the responses needed to shift from business as usual towards a safer and more just water future. Those framings involve water flows and limits; water rights and responsibilities; water values and prices; and, finally, green and grey water infrastructure. Here Quentin and Safa discuss why it is so important to acknowledge and the growing challenge of too much, too little, and too dirty water.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Last month, July 2023, saw global warming records toppled everywhere. As worrying as that is, it’s just a ‘dress rehearsal’ for what is to come in terms of impacts relating to accelerating climate change. If you include what humanity is doing to biodiversity, the overextraction and misuse of water, and on-going injustice, especially to impoverished communities, this means we have an unsustainable future and a recipe for disasters.

Our review, however, is not another ‘doom-and-gloom’ story arguing that the world needs fixing (though it does!) and that we need to reduce humanity’s carbon and water footprints (among many other impacts). Instead, it’s a wake-up call to those who don’t yet know that the climate crisis will be coming to their front doors (if it’s not already there) with ‘too much, too little and too dirty’ water (Grafton and Fanaian, 2023).

This means that while we must stabilize (and then reduce and lock up) greenhouse emissions, we have another task at hand that is just as pressing and connected; we need to respond to the global water crisis. Unlike the carbon cycle which has long lags, the flux of the water cycle is much more rapid. This gives us all the opportunity to make speedier improvements in water availability, access, quality, and sustainability, should we choose to act.

The challenge, as with mitigating carbon emissions, is that moving from business as usual comes with costs. Some of the losers are those who benefit from the status quo; people who, in response, either stop or slow down change. This is why narrative to counter delay, post-truth and obfuscation is critically important.

The first step to deliver transformational change and to move away from business as usual is to ‘face the facts’ and to recognise the causes and consequences of the world water crisis problem.

The second step is to ‘act on the facts’ and to deliver the solutions. This is because without change many people in both rich and poor countries are going to suffer in a big way from ‘too much, too little, too dirty’ water; and that suffering is set to dramatically increase with accelerating climate change.

Too much, too little, too dirty

Too much water is primarily about flooding events that expose at least 20 percent of humanity to flood risks. Globally, between 2001 and 2010, there were around 1,700 large-scale flood events that generated total damages of US$276 Billion (adjusted for inflation). By comparison, between 2011 and 2020 there were some 1,500 flood events with reported damages of US$481 billion.

In coastal areas, too much water from storm surges exacerbates saline intrusion associated with sea-level rise. Too much water is not just a result of excess precipitation but is caused by land-use planning that unnecessarily exposes people to flood risks, inadequate or improper infrastructure that transfers downstream and coastal flooding risks (sometimes magnifying the risks), and the degradation of green infrastructure (eg, wetlands loss, deforestation, etc).

Too little water is primarily about hydrological droughts that arise from both meteorological and human actions, such as excessive water withdrawals. Too little water also includes the limited water access of billions of people due to exclusion from formal piped water systems and/or from the high economic costs of access to safe water supplies.

Too dirty water is about water pollution; most visible with inadequate Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) pollution of water bodies. Too dirty water means that globally some 2 billion people are forced to drink unsafe water which has a disproportionate negative impact on both children and women. Failing to deliver safe water and sanitation causes premature deaths, globally, of more than one million people per year and widespread morbidities associated from water-borne diseases and parasites (e.g., cholera, dysentery, schistosomiasis, etc). A global study on the burden of disease shows that unsafe water sources led to as many as 1.7 million deaths in 2017 and caused disabilities (Disability-adjusted life years) for more than 87 million.

From crisis to justice

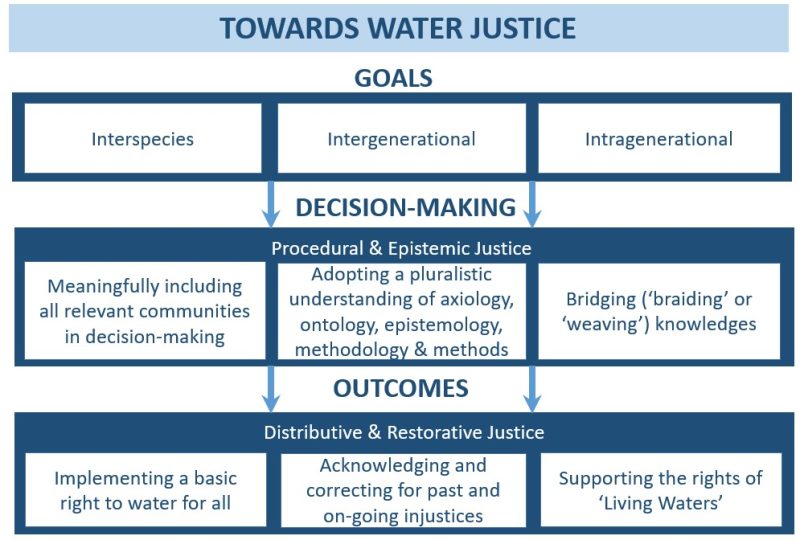

Connecting all three dimensions of the world water crisis is water justice. At a minimum, water justice requires: one, everyone’s basic water needs are met; two, procedural justice such that all those materially affected by water decisions have a respected ‘voice’ at the table; three, substantive and restorative justice such that actions are taken to correct for past and continuing water injustice; four, epistemic justice such that decision-makers value and respect all knowledges and experiences; and, five, justice for ‘living waters’ that goes beyond an exclusive anthropogenic and/or utilitarian view of water. These five underpinnings of water justice are consistent with the goals of Interspecies, Intergenerational and Intragenerational justice (Figure 1).

How we respond to the world water crisis and what should be prioritised to remedy it has been the subject of much debate, including at the UN 2023 Water Conference and its Water Action Agenda. In our view, multiple and context-specific responses from the local to the global are required to respond to the challenges of ‘too much, too little and too dirty’ water.

We highlight five priorities: one, prioritising and investing in delivering the basic right to water for all; two, financing investments and establishing planning, regulations and incentives to reduce the impacts of flooding and hydrological droughts; three, monitoring and reducing water pollution via vigilant regulation and the pricing of ‘bads’; four, measuring the ‘what, which, when and for whom’ of how water is consumed and to apply both regulations and incentives to cap water consumption where it is unsustainable; and five, pro-active conservation of natural capital (eg, wetlands, upstream forests) and invest in human and social capital that are critical to a safer and more just water future.

‘Turning the Titanic’ of the world water crisis will require facts, not just opinions, and evidence rather than rhetoric. Importantly, it demands a fact-based narrative as to why the world needs to move away from business as usual and that highlights the costs of inaction and delay. Ultimately, the world needs transformational pathways and investments in better governance and in green and grey infrastructure to create ‘positive tipping points’ when relatively small interventions and actions lead to large impacts. This is a huge global challenge but it is not insurmountable; “Start by doing what’s necessary; then do what’s possible; and suddenly you are doing the impossible”.

References

Grafton RQ & S Fanaian (2023). ‘Responding to the Global Challenges of ‘Too Much, Too Little and Too Dirty’ Water: Towards a Safer and More Just Water Future’ Notas Económicas, July 2023: 65-90.

https://impactum-journals.uc.pt/notaseconomicas/article/view/13258

Grafton RQ, J Gupta, A Revi, M Mazzucato, N Okonjo-Iewala, J Rockström, T Shanmugaratnam, Y Aki-Sawyerr, A Bárcena Ibarra, LT Cantrell, MF Espinosa, A Ghosh, N Ishii, JC Jintiach, B Qui; M Ramphele, MR Urrego, I Serageldin, R Damania, K Dominique, D Esty, HWJ Ovink, U Rao-Monari, A Selassie, LS Andersen, YA Beejadur, H Bosch, LK von Burgsdorff, S Fanaian, J Krishnaswamy, J Lim, M Portal, N Sami, J Schaef, A Bazaz, P Beleyur, S Fahrlander, K Ghoge, KVS Ragavan, M Vijendra, K Wankhade, M Zaqout, A Dupont, X Lefaive & I Réalé (2023). The What, Why and How of the World Water Crisis: Global Commission on the Economics of Water Phase I Review and Findings. DOI 10.25911/GC7J-QM22. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/285201

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Quentin Grafton is a Professor of Economics at the Australian National University (ANU), Convenor of the Water Justice Hub, and the Executive Editor of the Global Water Forum.

Safa Fanaian is a Post-doctoral Research Fellow at the Crawford school of Public Policy at the Australian National University (ANU).

The views expressed in this article belong to the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Global Water Forum, the UNESCO Chair in Water Economics and Transboundary Water Governance, UNESCO, the Australian National University, World Bank, Oxford University, or any of the institutions to which the authors are associated. Please see the Global Water Forum terms and conditions here.

Banner image: Too much, too little and too dirty water is coming to a town near you very soon (if it hasn’t already arrived). (Image by Dean Moriarty from Pixabay)